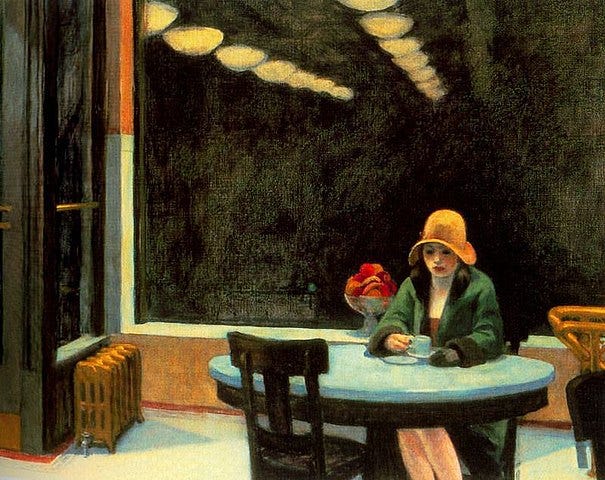

[…] As a rabbi, I see people in all sorts of situations and for all sorts of reasons, and one of the difficulties that people describe, sometimes masking it or confusing it with other symptoms, is a profound sense of loneliness. Where does it come from?

One way of understanding what’s going on is to see it as a logical reaction to the what everyday life has become in 2024. The cumulative effect of fear of terrorism, fear of antisemitism, fear of contaminating others or getting sick, ecological guilt about the effects of our actions, zero-waste culture, bad weather, bad public transport, rising cost of everything, the possibility of home-office, as well as the empty addictive behaviours around smartphones and social media — all of these together reduce any desire to ever leave home. The Covid lockdowns were an intensification of this phenomenon of self-isolation which started before and has continued since then1. On the whole, I’m an optimist and some of these factors, on their own, are positive things. Maybe it’s one of the features of Jewish life in France and around the world, over the last year, this feeling of loneliness. It’s something that people have confessed to me, the impossibility of sharing the complexity of our emotions with others around us, and the increasing lack of desire to try to do so. And it’s also a feature of the modern condition: Jews, non-Jews, people living alone and those in couples and families, there’s a growing epidemic of loneliness.

I say this to a group of people who have gathered together here on Yom Kippur, and it’s thus not the only feature of our lives or of this day. But there is something in Yom Kippur itself that lends itself to a sense of aloneness, if not also loneliness. As much as we are pushed to gather together in the synagogues for impossibly long prayers, the central mission of the day, teshuva, is meant to take place in our hearts and mind. The whole idea of standing before this divine judgement is that nobody else can know if we’re being honest with ourselves. Are we happy with the way we act, are we sorry for what we’ve done, do we really want to change? We can say the words, we can sing and beat our chests, but essentially on this day we stand alone before God — or even more terrifying, we simply stand alone.

When we read the long description of the High Priest on Yom Kippur, we get a similar sense of someone alone surrounded by people. The Kohen Gadol is the main protagonist of this day; indeed, it’s the one day a year that he had a particular function, otherwise he was basically like the other priests. And although he prepares for seven days before Yom Kippur, and he’s surrounded by people all night so that he doesn’t sleep, and he’s running around all day preparing the sacrifices and sending the scapegoat out to the desert — the climax of the day is when he is alone in the Holy of Holies. What does he do there, surrounded by smoke and darkness? We don’t know exactly. The Mishna says that he would say a short prayer, and later sources try to guess what it was, but the truth is that the inner world of the High Priest is as much a mystery as the Holy of Holies, and as much a mystery as the inner world of everyone else in the world. Can we look at the others around us and know what pain they’ve had to suffer, what dreams they’ve never yet fulfilled? If you read carefully the verses describing Aaron, the first High Priest, entering the sacred space, you'll realise that it comes straight after the loss of his two sons, and he carries the silence of grief with him.

There have been repeated calls this past year for coming together, for standing together, for unity. Maybe it's an acknowledgement of and a reaction to this epidemic loneliness: we need to be united. In the first weeks of October, I think that many people in the Jewish world felt something of this instinctive solidarity; hearts opened up and volunteers materialised and displaced people were housed, we sent messages to each other to check in, and sent back pictures of hearts and broken hearts. When it happens organically like that, we’re struck by the beauty of this possibility, that loneliness can be overcome by chesed, by love. I’m reminded of the words of the Yom Kippur prayer, a hopeful description of a perfect world:

וְיֵעָשׂוּ כֻלָּם אֲגֻדָּה אֶחָת לַעֲשׂוֹת רְצוֹנְךָ בְּלֵבָב שָׁלֵם.

May all become one gathering, doing Your will wholeheartedly.

But when I compare these experiences to the invitations by politicians to ‘be united’, their calls feel hollow and shallow. I think the difference between unity that just happens, and a forced unity, has to do with ego. Very often, everyone wants unity but nobody wants to compromise.

Back to the High Priest on Yom Kippur, we read of three rounds of confessions. First he asks for atonement for himself and his close family, then for his tribe, and finally for the entire people. This seems to be a good model for us too. We live in concentric circles of responsibility, and starting with ourselves and moving outwards makes sense. Rabbi Israel Salanter, the founder of the Musar movement in 19th-century Lithuania, supposedly told the following tale:

“When I was a young man, I wanted to change the world. I found it was difficult to change the world, so I tried to change my nation. When I found I couldn't change the nation, I began to focus on my town. I couldn't change the town and as an older man, I tried to change my family. Now, as an old man, I realize the only thing I can change is myself, and suddenly I realize that if long ago I had changed myself, I could have made an impact on my family. My family and I could have made an impact on our town. Their impact could have changed the nation and I could indeed have changed the world.”

It’s much easier to talk about changing oneself than to actually do it, of course. My transgressions define who I am more than anything else. But nonetheless, we are called on Yom Kippur to find the courage to at least contemplate an alternative life. I imagine the High Priest in this kind of process. He comes out of the Holy of Holies, but also the Lonely of Lonelies, and whispers a confession that we will never hear. Yom Kippur can’t continue if this doesn’t happen — if the High Priest was a sinless saint, there would be no Yom Kippur possible for anyone. He then reconnects to his family, tribe and people, acknowledging their imperfections and asking for them to be overlooked, once again, this year.

In theory, it would be tempting to say that a connection to community is the antidote both for the loneliness that the modern world pushes us into, and to the hollow calls for unity that we hear. I want to say: Community, not unity. People caring for each other, despite and because of their differences and the acknowledgement of their imperfections. We have seen something of this possible community this year, in and around Adath Shalom and in different places in the Jewish world, in the world at large. It’s my dream, and my wish for us, that we manage to build and reinforce the communities around us, that don’t negate the individuals within it and have a place for personal development, each person on their own journey of development. But I want also to give a place to loneliness, which is real and will not disappear any time soon, and want to conclude by acknowledging it once again. Yom Kippur is ultimately a lonely event, that takes place in the heart rather than in the synagogue. Each person is a reflection of the High Priest, standing alone before God and before themselves. We shout out the same words of prayer, but nobody knows what is happening in the minds of the person sitting next to them, their pain and their hopes. I don’t want to present this loneliness as a tragedy, neither to romanticise it, but just — tonight, Yom Kippur — to acknowledge its reality. Welcome, loneliness, welcome, lonely people. May we use this coming day to bring ourselves, honestly and exactly as we are, and together build a community of care, whose effects will ripple out through the entire world.

I will finish by repeating that Yom Kippur is a powerful day, but not a sad one. I finish by wishing you all Shabbat shalom, Hag Sameah, and Gmar Hatima Tova!

[I share here the diagnostic but not the conclusions of Pascal Bruckner.]