You might remember that last week’s parasha ended with a long list of names of the twelve tribes and eight kings, descendants of Esau. Now, the story returns to Jacob, and we’re introduced to the new hero who will accompany us until the end of the book, Joseph. But the Jewish tradition is very sensitive to this sudden jump back to Jacob’s story, and tells a strange story to link these two chapters.

וישב יעקב, הַפִּשְׁתָּנִי הַזֶּה נִכְנְסוּ גְמַלָּיו טְעוּנִים פִּשְׁתָּן, הַפֶּחָמִי תָמַהּ אָנָה יִכָּנֵס כָּל הַפִּשְׁתָּן הַזֶּה? הָיָה פִּקֵּחַ אֶחָד מֵשִׁיב לוֹ נִצּוֹץ אֶחָד יוֹצֵא מִמַּפּוּחַ שֶׁלְּךָ שֶׁשּׂוֹרֵף אֶת כֻּלּוֹ, כָּךְ יַעֲקֹב רָאָה אֶת כָּל הָאַלּוּפִים הַכְּתוּבִים לְמַעְלָה, תָּמַהּ וְאָמַר מִי יָכוֹל לִכְבֹּשׁ אֶת כֻּלָּן? מַה כְּתִיב לְמַטָּה, אֵלֶּה תּוֹלְדוֹת יַעֲקֹב יוֹסֵף, דִּכְתִיב וְהָיָה בֵית יַעֲקֹב אֵשׁ וּבֵית יוֹסֵף לֶהָבָה וּבֵית עֵשָׂו לְקַשׁ (עובדיה א') – נִצּוֹץ יוֹצֵא מִיּוֹסֵף שֶׁמְּכַלֶּה וְשׂוֹרֵף אֶת כֻּלָּם:

AND JACOB ABODE: The camels of a flax dealer once came into a city laden with flax. A blacksmith asked in wonder where all that flax could be stored, and a clever fellow answered him, “A single spark caused by your bellows can burn up all of it.” So too, when Jacob heard of all the chiefs whose names are written above he said wonderingly, “Who can conquer all these?” What is written after the names of these chieftains? “These are the generations of Jacob — Joseph”. For it is written (Obadiah 1:18) “And the house of Jacob shall be a fire and the house of Joseph a flame” — one spark issuing from Joseph will burn up all of these descendants of Esau. (Rashi on Genesis 37:1)

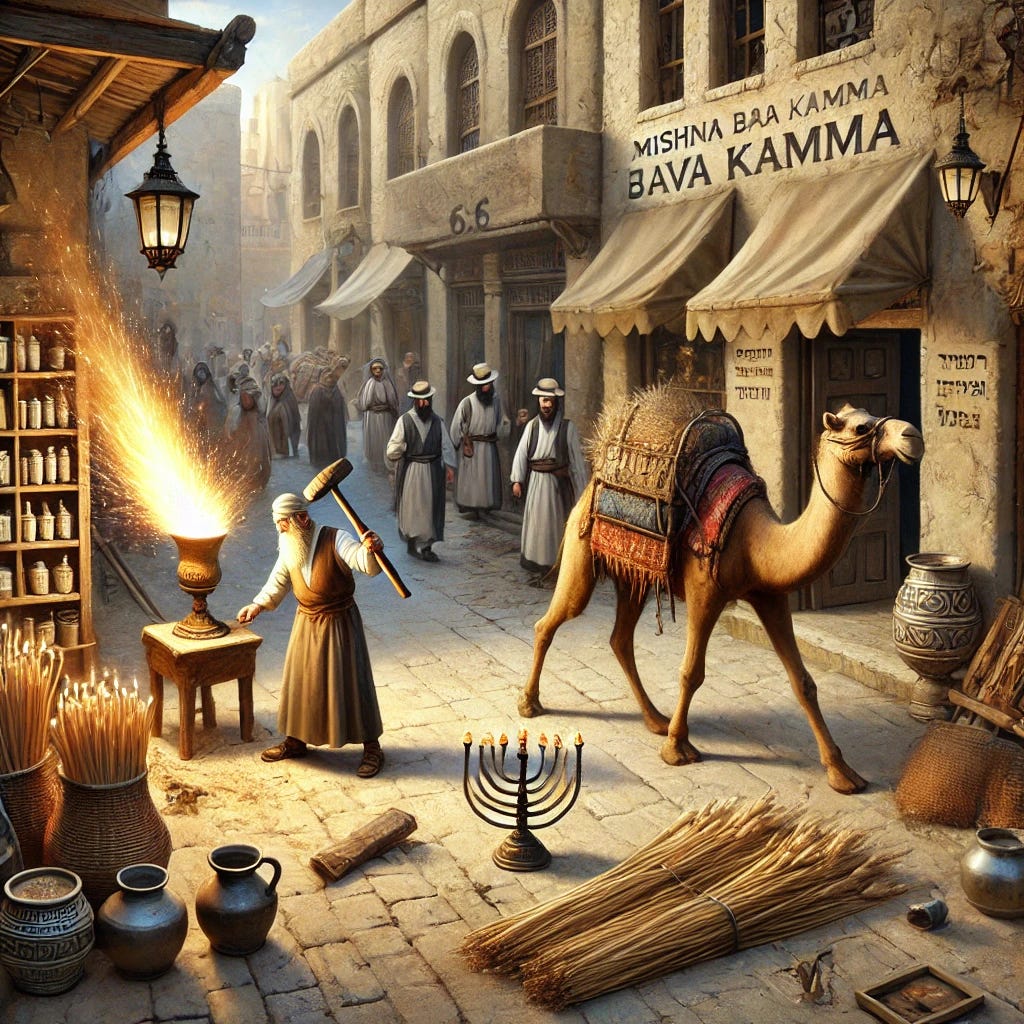

On its own, it’s an interesting angle. The rabbinic tradition doesn’t believe that the two brothers, Esau and Jacob, really made peace when they finally met, and prefers to see them as eternal enemies. Here, then, the mention of the descendants of Esau is supposed to provoke fear in Jacob — until he learns that Esau’s might is ephemeral and that his own youngest son, Joseph, could destroy them. All that is interesting in itself (maybe), but these mentions of flax and sparks and flames are also very reminiscent of the upcoming festival of Chanukah. Chanukah is hardly mentioned in the Mishna, but one of the few references to it is not where you might expect: rather than in the context of a discussion of ritual practices, it’s in the tractate of Bava Kama, dealing with compensation for damages caused by fire. I quote:

גֵּץ שֶׁיָּצָא מִתַּחַת הַפַּטִּישׁ וְהִזִּיק, חַיָּב. גָּמָל שֶׁהָיָה טָעוּן פִּשְׁתָּן וְעָבַר בִּרְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים, וְנִכְנַס פִּשְׁתָּנוֹ לְתוֹךְ הַחֲנוּת, וְדָלְקוּ בְּנֵרוֹ שֶׁל חֶנְוָנִי וְהִדְלִיק אֶת הַבִּירָה, בַּעַל הַגָּמָל חַיָּב. הִנִּיחַ חֶנְוָנִי נֵרוֹ מִבַּחוּץ, הַחֶנְוָנִי חַיָּב. רַבִּי יְהוּדָה אוֹמֵר, בְּנֵר חֲנֻכָּה פָּטוּר:

If a spark flew out from under one’s hammer and caused damage, that person is liable. If a camel laden with flax passed by in the public domain and its load of flax entered into a shop and caught fire, the owner of the camel is liable. But if the shopkeeper left his lamp outside, the shopkeeper is liable. Rabbi Judah says: “If, however, it was a Hannukah lamp outside, he is not liable.” (M Bava Kamma 6:6)

The Hannukah candle is dangerous, and there is always a risk taken by bringing it into the public domain. Anyone in this country who has the dilemma of where to light the Hanukkiah feels this instinctively: should we light it in the window or on the balcony, as we are supposed to, or inside the house, as we are permitted to do in times of danger? If it’s placed on the boundary of the private and the public spheres, it performs its function of advertising the miracle that happened to us, of showing our healthy pride in who we are to others. When it’s hidden completely in the house, we lose the possibility of interaction with the outside world. If it’s completely in the public and not connected to the home, like the Chabad sect have started doing, it’s a message without content (and forbidden, according to most halachic authorities). The ideal place is on the boundary of the inside and the outside. But even there, like with the candle of the shopkeeper, the outside world can react badly to this light. A flame can be used to destroy or to create, to blind or to illuminate. Sending sparks out into the world can be a byproduct of creating something, or an act of destruction. Going back to Joseph, the whole tension of his story revolves around his experiences of revealing his light, revealing the sparks of inspiration in his dreams and in those of others; or covering his light in a pit, in prison, disguised as an Egyptian.

This idea of creating and using sparks has deep roots in the Jewish sources. In the kabbalistic model of the world, sparks of the primordial light of creating are trapped in everything, and the task of humanity in general and of Jews in particular is to discover these holy sparks and liberate them. Jewish spirituality is not only found in the synagogue or the Temple, but in the home and the workplace and on the street: the halacha deals with these places because they are important, because there are hidden sparks and a potential for holiness there. In the same way that we can transform oil or wax into light and proclaim a miracle, through the right actions and intentions we can transform every situation into one that manifests the presence of God. But there’s a risk involved when playing with fire — I am reminded of Levinas’ claim that Judaism is “a religion for adults”. In the story of Chanukah, for example, one of the main tensions is the relationship to Greek culture. There were certain zealots who rejected it completely. There were attempts to draw on the best of Greek philosophy and science and bring them into the Jewish world. And there were the mityavnim, those who assimilated completely into Greek culture, covered up any sign of their Judaism, and burned up entirely in trying to liberate these sparks.

One of the messages I hear from the story of Joseph, which is always read on the Shabbat before Chanukah, is about being masters of our sparks and flames. We can have the courage to be absolutely in the world, in the places that seem least holy, because we can rely on the light that we find within ourselves and the lights that we reveal in others around us. Our dreams have the power to illuminate the world, and we need to know how and when to share them. We should know both the risk of encountering the outside world, and the dangerous power involved in the light we carry: we can burn others, if we lose control. And more than anything else, we need to appreciate the importance of the home for Chanukah: we need to have a home in order to place the lights and let them shine outwards, we need to have a Self in order to encounter, and we need to have a message with content in order to be able to proclaim it. This week, the week of the winter solstice and long dark nights, may we learn to recognise and master the lights of the world. May we find the sparks of holiness and of inspiration, in ourselves and in others, and let the Chanukah lights illuminate inside and outside.

Shabbat shalom!

[If you’re looking to read more about Chanukah, last year I wrote a fairly long commentary on the classic laws of the festival, and you can read it here. I also recently did an experiment, and fed everything I’ve ever written about Chanukah to an AI avatar, which is now set up to respond to questions about the festival and in theory should answer like me. If you’d like to participate in the experiment, you can try it out here (you might need to open a free account to use it). Please let me know what you think!]