I want to also acknowledge the fear and anger among Jewish communities after the attacks on Israeli football fans in Amsterdam last night. That there was provocation on both sides doesn’t detract from the traumatic reactions we all have to seeing these images of gangs looking for Jews to beat up in the street. And for some people I’ve spoken to, the question of Jewish public visibility is being discussed again: should we stand out or try to blend in?

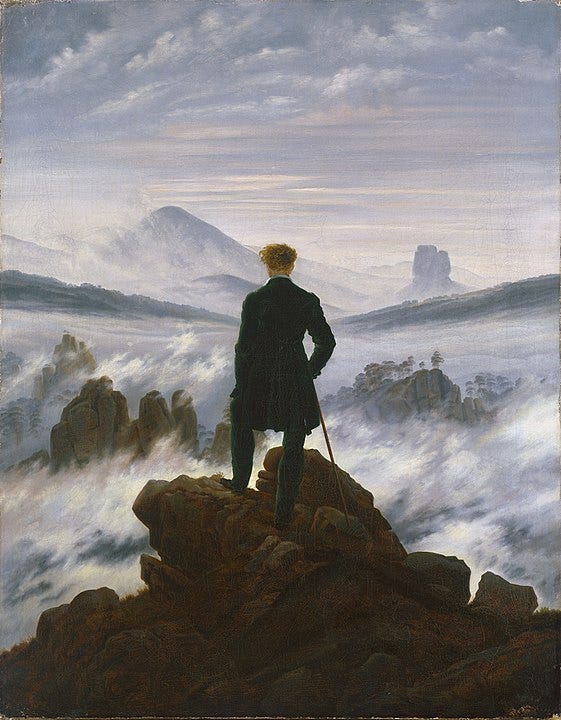

In this week’s parasha, we meet the hero of the rest of the book of Bereshit, the man who will be known as Abraham. The tradition emphasises his singularity, and possibly his loneliness too. אחד היה אברהם, “Abraham was one,” says the prophet Ezekiel. He’s known as the Ivri, the Hebrew, which one midrash identifies with the word Ever, the bank of the river.

רבי יהודה אומר: כל העולם כולו מעבר אחד והוא מעבר אחד

Rabbi Yehuda explains that the entire world was one one side of the river, and Abraham was on the other. (Bereshit Rabbah 42)

What was this singularity? A hassidic tradition says that Abraham was known as ‘one’ because he understood the singularity of God, Adonai Echad. It was this rejection of idolatry that separated him from the society around him. Maimonides emphasises that the whole idea of idolatry was a confusion that developed after the flood, when people confused the creations of God with the creator, and started worshipping the sun and stars. Abraham figured out alone that God was one, beyond all the symbols and statues (the midrash says that his two kidneys were his teachers; he had literally a ‘gut feeling’ about the way the world worked.) I hesitate to call this understanding ‘monotheism’, because in my understanding, when we say things like Adonai Echad, ‘God is one’, we’re not only making an arithmetic declaration, that God is not three or ten, but declaring a relationship: ‘You are the one for me’. But the rejection of idolatry is more than that, it’s a rejection of falsehood, deception and misguided passion, and again, in the midrashic retelling of the story, Abraham paid the price for holding on to these counter-cultural convictions by being cast into the fire by King Nimrod, and losing his younger brother.

What did Abraham do with his new comprehension of the world, his rejection of idolatry and relationship with the One God? Our parasha begins with Abram being told to leave his home and go to the land of Canaan, but at the end of last week’s reading, he had already left his home and was temporarily living in Haran. When he hears the call of Lech Lecha, go for yourself, he leaves Haran with everyone in his household. The verse says:

וַיִּקַּ֣ח אַבְרָם֩ אֶת־שָׂרַ֨י אִשְׁתּ֜וֹ וְאֶת־ל֣וֹט בֶּן־אָחִ֗יו וְאֶת־כׇּל־רְכוּשָׁם֙ אֲשֶׁ֣ר רָכָ֔שׁוּ וְאֶת־הַנֶּ֖פֶשׁ אֲשֶׁר־עָשׂ֣וּ בְחָרָ֑ן וַיֵּצְא֗וּ לָלֶ֙כֶת֙ אַ֣רְצָה כְּנַ֔עַן וַיָּבֹ֖אוּ אַ֥רְצָה כְּנָֽעַן׃

Avram took Sarai his wife and Lot his brother’s son, all their property that they had gained, and the persons whom they had made-their-own in Harran, and they went out to go to the land of Canaan. (Genesis 12:5, Translation: Everett Fox)

The midrash picks up on the strange formulation in the verse regarding the persons or the ‘souls’ that they ‘made’, and understands that they converted a group of people around them in that city, and this whole community came with them to the land of Israel. Usually we say that Judaism is not a proselytising religion, and doesn’t actively try to convert others. On the whole that’s true, and yet we have traditions regarding Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, as well as Sarah, that say that they would gather converts around them wherever they went (Bereshit Rabbah 84). But all these traditions are very weird. What did it mean to convert, when there was no religion and almost no commandments? Abram himself hadn’t yet been circumcised, so what was it that the ‘souls he made’ were taking upon themselves? It must be that they were convinced of his convictions that idols were false, and that they committed, like Abram, to a relationship with one God. From the language of the midrash, it sounds like he was active in this process: speaking his truth even though it was against the majority of the people around him.

This seems to be an inspiration to us today, in an age where truth is rare and the distortion of the world, modern-day idolatry, is rampant. When heads of states manipulate language to whip up the ugliest primal emotions of fear and hate, and work to tear down the structures of democracy and civilisation. Standing up, even as a minority, to such idolatry is the heritage of Abraham, and all the spiritual children of Abraham are called to emulate. This is even more relevant in an age where information is a commodity mined by companies. More and more people are interacting with their computers through the medium of artificial intelligence, which gets its intelligence by what its algorithms are able to find and deem authoritative. If you ask ChatGPT a question about Judaism, very often the answer is in the style of Chabad, a fringe sect in the Jewish world that has a large online presence. That’s why I make an effort to put as much of my writing up on the synagogue website, not only for the people who read directly but also to add my voice to the noise that the algorithms are channeling to the world.

But I want to complicate things just a little bit. One of the beautiful aspects of reading the Torah in the original Hebrew is the ability to pick up on small nuances in the grammar. Many of us know that one of God’s names, Elohim, has a plural suffix but is treated grammatically as singular — we translate it as God rather than ‘gods’. But very occasionally, it is followed by a plural verb in which case it actually is more correct to understand it as ‘gods’. When Abraham speaks to the pagan king Avimelech and tells his story, he says וַיְהִ֞י כַּאֲשֶׁ֧ר הִתְע֣וּ אֹתִ֗י אֱ-לֹהִים֮ מִבֵּ֣ית אָבִי֒ (Genesis 20:13). Almost all translators (with the rare exception of Robert Alter), translate this as usual in the singular: ‘When God made me wander away from my ancestral land’. But a sensitive and more accurate translation would follow the Hebrew verb in the plural, and translate ‘When the gods made me wander away’. Why would Abraham speak like this: Abraham the one, the person not afraid to speak the truth and negate idolatry and polytheism?

The fact that Abraham is able to nuance his language, speak of one God in some contexts but of multiple gods in others, is to me a sign of his political pragmatism. He is brave enough to argue with God, but arguing with a pagan king is not worth his time and counterproductive. I don’t see Abraham as manipulative in his language here, just choosing his battles, and when I said that we should be inspired to be speaking the truth in an age of post-truth, again I see Abraham as the model of nuance, sensitivity and context. The Talmud discusses the appropriateness of saying the right thing before people who are unable or unwilling to listen.

וְאָמַר רַבִּי אִילְעָא מִשּׁוּם רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר בְּרַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן: כְּשֵׁם שֶׁמִּצְוָה עַל אָדָם לוֹמַר דָּבָר הַנִּשְׁמָע — כָּךְ מִצְוָה עַל אָדָם שֶׁלֹּא לוֹמַר דָּבָר שֶׁאֵינוֹ נִשְׁמָע. רַבִּי אַבָּא אוֹמֵר: חוֹבָה, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״אַל תּוֹכַח לֵץ פֶּן יִשְׂנָאֶךָּ הוֹכַח לְחָכָם וְיֶאֱהָבֶךָּ״.

Rabbi Ile’a said in the name of Rabbi Elazar, son of Rabbi Shimon: Just as it is a mitzva for a person to say that which will be heeded, so is it a mitzva for a person not to say that which will not be heeded. Rabbi Abba says: It is obligatory for him to refrain from speaking, as it is stated (Proverbs 9:8): “Do not reprove a scorner lest he hate you; reprove a wise man and he will love you” . (Yevamot 65b)

It is difficult and perhaps impossible to know how to make these decisions, not knowing who might be listening and touched by what we have to say. We also might doubt whether we have the truth ourselves, whether its important to stand out. But if we have these struggles about what to say to whom and how always trying to maximise truth and to do the right thing, then these struggles in themselves are probably a good sign of being in the path of Abraham.

Shabbat shalom!